Miloš Šejn | Českých Bratří 312 | CZ-50601 Jičín | T +420 723 701 658 | milos [at-sign] sejn.cz

AllForWeb | © 2008 sejn

Disk cannot be read

Disk cannot be read Místa snivců / Lenka Falušiová & Miloš Šejn

Místa snivců / Lenka Falušiová & Miloš Šejn Ani labuť ani Lůna

Ani labuť ani Lůna ZATVÁŘÍ / COUNTENANCE

ZATVÁŘÍ / COUNTENANCE Silent Spring: Art and Nature 1930–1970

Silent Spring: Art and Nature 1930–1970 Creation – Myth – Art

Creation – Myth – Art DIVERSITY CONTEMPORARY II

DIVERSITY CONTEMPORARY II PAF 2024 / DIARIES - Deposit of Memory: Video Works by Miloš Šejn from 1988-2022

PAF 2024 / DIARIES - Deposit of Memory: Video Works by Miloš Šejn from 1988-2022 THROUGH THE LABYRINTH

THROUGH THE LABYRINTH LANDSCAPE FESTIVAL PRAGUE 2024

LANDSCAPE FESTIVAL PRAGUE 2024 ANIMA MUNDI | VISIONS – ITSLIQUID INTERNATIONAL ART FAIR | VENICE 2024

ANIMA MUNDI | VISIONS – ITSLIQUID INTERNATIONAL ART FAIR | VENICE 2024 MEMORY DEPOSIT

MEMORY DEPOSIT KOR . KON . TOI . 0 0 1 – Miloš Šejn / Adriena Šimotová

KOR . KON . TOI . 0 0 1 – Miloš Šejn / Adriena Šimotová BECOMING GARDEN…

BECOMING GARDEN… Heraclitus principle / One hundred years of coal in Czech art

Heraclitus principle / One hundred years of coal in Czech art SYMBIOSIS

SYMBIOSIS 1 : 1 : 1

1 : 1 : 1 Wege in die Abstraktion im Dreiländereck II

Wege in die Abstraktion im Dreiländereck II BIRTHDAY

BIRTHDAY Face for SU–EN

Face for SU–EN Valoch & Valoch / Archeology And Conceptual Art

Valoch & Valoch / Archeology And Conceptual Art Wege in die Abstraktion im Dreiländereck

Wege in die Abstraktion im Dreiländereck AQVA

AQVA KINETISMUS: 100 Years of Electricity in Art

KINETISMUS: 100 Years of Electricity in Art EMERGENCY EXIT

EMERGENCY EXIT MAN IN THE CAVE

MAN IN THE CAVE ÍHMNÍ

ÍHMNÍ SEMI-OPEN

SEMI-OPEN Zdzisław Jurkiewicz. Occurrences

Zdzisław Jurkiewicz. Occurrences Art Safari 36: TOGETHER

Art Safari 36: TOGETHER ART, MELANCHOLY AND LAUGH FACES IN THE FACE OF ABSURDITY

ART, MELANCHOLY AND LAUGH FACES IN THE FACE OF ABSURDITY KRAJINA + / LANDSCAPE +

KRAJINA + / LANDSCAPE + WATER

WATER ATLAS NEW CONSTELLATIONS

ATLAS NEW CONSTELLATIONS FOR THE LAST FIFTY YEARS

FOR THE LAST FIFTY YEARS PILGRIMAGE TO THE MOUNTAINS

PILGRIMAGE TO THE MOUNTAINS Fotograph Festival #X UNEVEN GROUND

Fotograph Festival #X UNEVEN GROUND Í T H M N

Í T H M N Table and Territory / Table et Territoire

Table and Territory / Table et Territoire Looking Into The Window

Looking Into The Window A Pilgrim Who Returns

A Pilgrim Who Returns

Gočár Phenomenon

Gočár Phenomenon ART SAFARI 35 – HYDRANT

ART SAFARI 35 – HYDRANT 24h PERFORMANCE

24h PERFORMANCE Through the Landscape of K. H. Mácha

Through the Landscape of K. H. Mácha NMHTÍ

NMHTÍ IDENTITY

IDENTITY Homeplace & Kunka Phenomenon

Homeplace & Kunka Phenomenon ↗ ASCENT ↙ DESCENT / performance art event

↗ ASCENT ↙ DESCENT / performance art event Parallel cinema / Stream, Tree and Stone

Parallel cinema / Stream, Tree and Stone Ji.hlava

Ji.hlava TRA DUE MONDI

TRA DUE MONDI Pilgrims, Refugees, Hermits

Pilgrims, Refugees, Hermits The Naked Forms Festival (FNAF)

The Naked Forms Festival (FNAF) Sounds / Codes / Images - Audio Experimentation in the Visual Arts

Sounds / Codes / Images - Audio Experimentation in the Visual Arts rivers, streams, puddles

rivers, streams, puddles IL SORRISO DEL LEONE / VENICE TELEPATHIC BODIES

IL SORRISO DEL LEONE / VENICE TELEPATHIC BODIES Performance Crossings 2019

Performance Crossings 2019 THEATRUM MUNDI III

THEATRUM MUNDI III Early Manifestations of Action Art in East Bohemia

Early Manifestations of Action Art in East Bohemia AQVA MUO

AQVA MUO Yellow Rose Fragrance

Yellow Rose Fragrance WÄRMFLASCHE

WÄRMFLASCHE ART SPACE ECOLOGY

ART SPACE ECOLOGY Architecture and Senses

Architecture and Senses THEATRUM MUNDI II

THEATRUM MUNDI II OPERA CORCONTICA

OPERA CORCONTICA PRAGUE WILDERNESS – LANDSCAPE FESTIVAL PRAGUE 2018

PRAGUE WILDERNESS – LANDSCAPE FESTIVAL PRAGUE 2018 Energy of the initial line – gesture, rhythm, movement in contemporary Czech art

Energy of the initial line – gesture, rhythm, movement in contemporary Czech art IMAGE / BODY / SOUND

IMAGE / BODY / SOUND EVERY WANDERING ENDS IN THE BEGINNING

EVERY WANDERING ENDS IN THE BEGINNING (Post)Land Art and the Anthropocene

(Post)Land Art and the Anthropocene CS CONCEPTUAL ART OF THE 70s

CS CONCEPTUAL ART OF THE 70s SONIC SOLAR MOUNTAIN

SONIC SOLAR MOUNTAIN Bohemiae Rosa

Bohemiae Rosa HOW TO EXPLAIN IMAGES TO AN INVISIBLE INTERSPACE

HOW TO EXPLAIN IMAGES TO AN INVISIBLE INTERSPACE LAPSody 2017 – The Bubble

LAPSody 2017 – The Bubble ALCHEMIC BODY | FIRE . AIR . WATER . EARTH

ALCHEMIC BODY | FIRE . AIR . WATER . EARTH LIQUID ROOMS / THE LABYRINTH

LIQUID ROOMS / THE LABYRINTH LANDSCAPE

LANDSCAPE The Landscape, Art and Photography | Contemporary Artworks in the Landscape

The Landscape, Art and Photography | Contemporary Artworks in the Landscape Branches | Nature art – variations

Branches | Nature art – variations AGARA / Hommage à la Peinture

AGARA / Hommage à la Peinture SPEECH MELODIES

SPEECH MELODIES SELÉNÉ / BECOMING A LUNAR FACE TELEPATHICALLY

SELÉNÉ / BECOMING A LUNAR FACE TELEPATHICALLY FACIALITY

FACIALITY SOLAR MOUNTAIN

SOLAR MOUNTAIN MICHALEK / ŠEIN

MICHALEK / ŠEIN IL SORRISO DEL LEONE

IL SORRISO DEL LEONE FACIALITY / Space of the Memory and an Immediate Space

FACIALITY / Space of the Memory and an Immediate Space Faces / Face as the phenomenon in videoart

Faces / Face as the phenomenon in videoart ARCHIVES & CABINETS

ARCHIVES & CABINETS The Written Face for SU-EN

The Written Face for SU-EN Finally Together

Finally Together B/L – Dedicated to Carolus Linnaeus

B/L – Dedicated to Carolus Linnaeus BEING LANDSCAPE

BEING LANDSCAPE Gardening

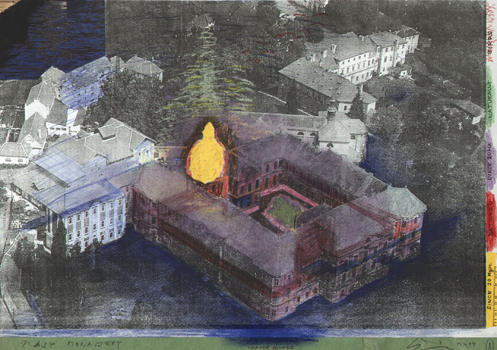

Gardening Cartusiae Waldiczensis

Cartusiae Waldiczensis LANDSCAPE UNDER TOTALITARIAN

LANDSCAPE UNDER TOTALITARIAN12.10.2018 - 14.10.2018

Milos Sejn: FUNGUS, division of sonic vibrations,1994

Milos Sejn: FUNGUS, division of sonic vibrations,1994  Milos Sejn: A NIGHTINGALE WITH A FLAT FLIGHT, PATH IN TRANSLATION, 2018

Milos Sejn: A NIGHTINGALE WITH A FLAT FLIGHT, PATH IN TRANSLATION, 2018

Academy Archives

Academy Archives

Miloš Šejn | Českých Bratří 312 | CZ-50601 Jičín | T +420 723 701 658 | milos [at-sign] sejn.cz